Eighteen forty-seven is a special year in flute history as Theobald Böhm (subsequently spelled “Boehm” for ease of typing) officially debuted his new flute design. But the Boehm system used today for flutes and other woodwinds was in fact developed a decade and a half before the midcentury blockbuster. Prior to the “1847 Boehm”, there was the “1832 Boehm”, and before that, the flute had undergone two centuries of redevelopment shaped by its ever-changing role and identity as an instrument.

Few written records existed pertaining specifically to flute construction prior to the fifteenth century, and no known medieval flutes have survived. If iconographical evidence is any aid, surviving paintings and sketches across cultures suggest that some version of the “Renaissance flute” had been a stable design for as long as people had been making music out of inanimate objects. Take a hollow tube of any length or shape, drill some holes into it, blow across the edge, and you’ve got yourself a flute.

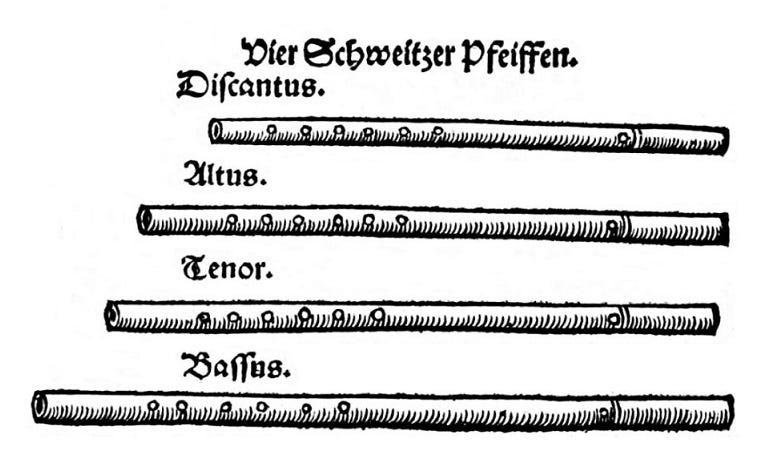

Extant specimens from the Renaissance period are scarce with authenticity issues abound. Currently, about 50 flutes from early 1500s to mid-late 1600s have been reasonably authenticated. While they differ in size and range, all conform to the basic design features that characterize the Renaissance flute: narrow keyless cylindrical bore in wooden construct with six small tone holes and one small embouchure hole. From specimens and written treatises, we know that these instruments were typically played in consorts consisting of bass flute in G, tenor/alto in D, and soprano/descant in A1. Because of their small tone hole sizes, the Renaissance flutes are significantly quieter than later designs, and in mixed ensemble playing with strings, voice, or other woodwinds, they were often doubled.

The prevalence of consort playing was emblematic of the Renaissance that marked a departure of the flute’s role as a military instrument. In the fifteenth century, the transverse flute was mainly used by Swiss and German soldiers during marches or on the battlefield and was often paired with the drum (hence the term Schweitzerpfeiff in German speaking countries and flûte allemande in France). Gradually, the Swiss pair, as they were known, made their way into court dances in Switzerland and other parts of Europe, and the music developed from simple monophonic tunes to highly sophisticated polyphony played with other wind instruments, often improvised. The earliest known surviving manuscript mentioning a flute consort is the four-part songbook Hubscher lieder by the Colognian publisher Arnt von Aich, printed sometime around or before 1520. Other leading theorists of the time who wrote extensively on the transverse flute and the Renaissance consort include Martin Agricola and Sebastian Virdung. Together, these song collections and treatises attest to the flute’s increasing significance beyond official and professional capacities into private lives as a popular amateur instrument during the sixteenth century.

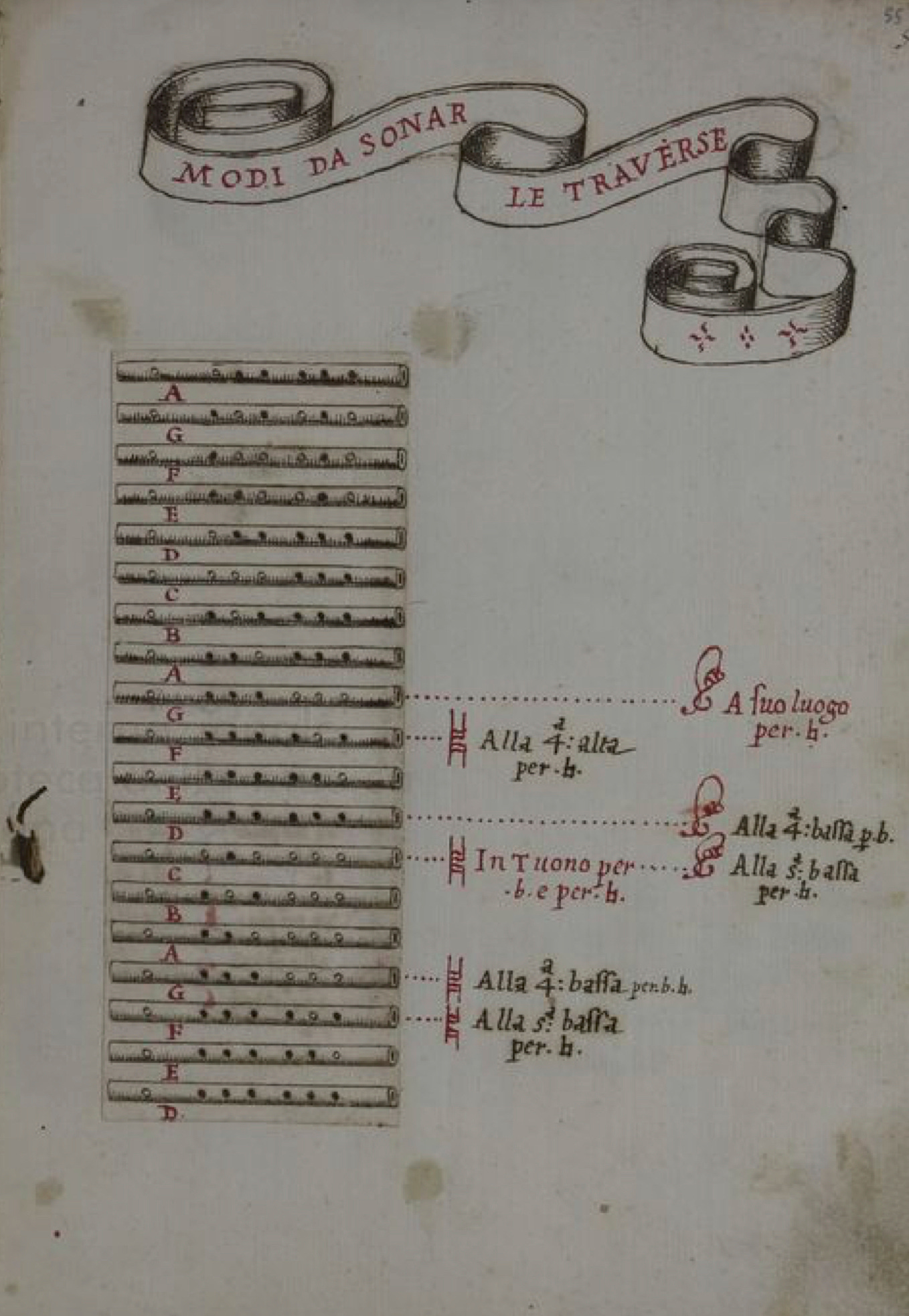

It is important to note that because tonal music was not developed until the Baroque period, the scale on a Renaissance flute is quite different from the modern idea of a major diatonic scale. Take the tenor flute in D, for example, a fingering chart from c.a. 1600 by the Italian theorist Aurelio Virgiliano shows the following:

Upon first reading, this fingering chart appears to be the D Dorian scale. This is not entirely surprising as the D final Dorian mode being the protus mode, or mode I, dates back to Medieval plainchant traditions. With some sources pointing to its origin in a six-stringed lyre from antiquity, the building block of Medieval and Renaissance musical scale is the six-note hexachord arranged in the tone-tone-semitone-tone-tone pattern. Beginning on the note C, the hexachordum naturale, or the natural hexachord, is as follows:

C - D - E - F - G - A

The Medieval Italian Benedictine monk, Guido of Arezzo, is today popularly credited with the invention of the solmization syllables ut (later changed to do)-re-mi-fa-sol-la based on the six notes of the hexachord. Guido is said to have taken the first syllables of the opening six lines of the hymn “Ut queant laxis” and assigned the notes of the hexachord to each vocable. The Guidonian system does not fix ut to the note C, but rather placing the only semitone in the hexachord between mi and fa. In other words, what matters in the Guidonian solmization isn’t the absolute pitch of a note, but the interval relationships between them, much like the movable do system of today.

Because the hexachordum naturale does not include the note B, a hexachord beginning on G is constructed to include the missing note:

G - A - B - C - D - E2

If we were to append the new note, B, to the end of the natural hexachord, we obtain

C - D - E - F - G - A - B

Note that the last four notes, F - G - A - B, form three consecutive whole tones, i.e. a tritone, which was carefully avoided throughout much of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance due to its highly dissonant quality. To mitigate this, several sixteenth and seventeenth century theorists have been found to offer solutions to alter the proceeding note, the most famous among whom was perhaps Michael Praetorius. In his voluminous 1619 treatise, Syntagma Musicum, Praetorius quotes a presumed then well-known Latin rhyme:

Una nota super la Semper est canendum fa A note above la Is always sung as fa

What this little couplet tells us is that when a note exceeds the sixth scale degree la (by a second), said note should be sung as a fa, i.e. a semitone away from the preceding note. That is to say, the oncoming note should be flattened. To allow for this flattened seventh note, a B♭, a third hexachord beginning on F is constructed:

F - G - A -B♭ - C -D

Because of the typographical shape of the note B in them, the G hexachord containing B♮ is called the hexachordum durum (hard hexachord, due to the square shape of the natural sign), and the F hexachord with B♭ is called the hexachordum molle (soft hexachord, due to the rounded flat sign). As an interesting aside, the German tonal nomenclature has inherited the dur and moll designations. In addition, the shape of ♮ has morphed into the letter H in the German musical alphabet where H refers to B♮ and B refers to B♭.

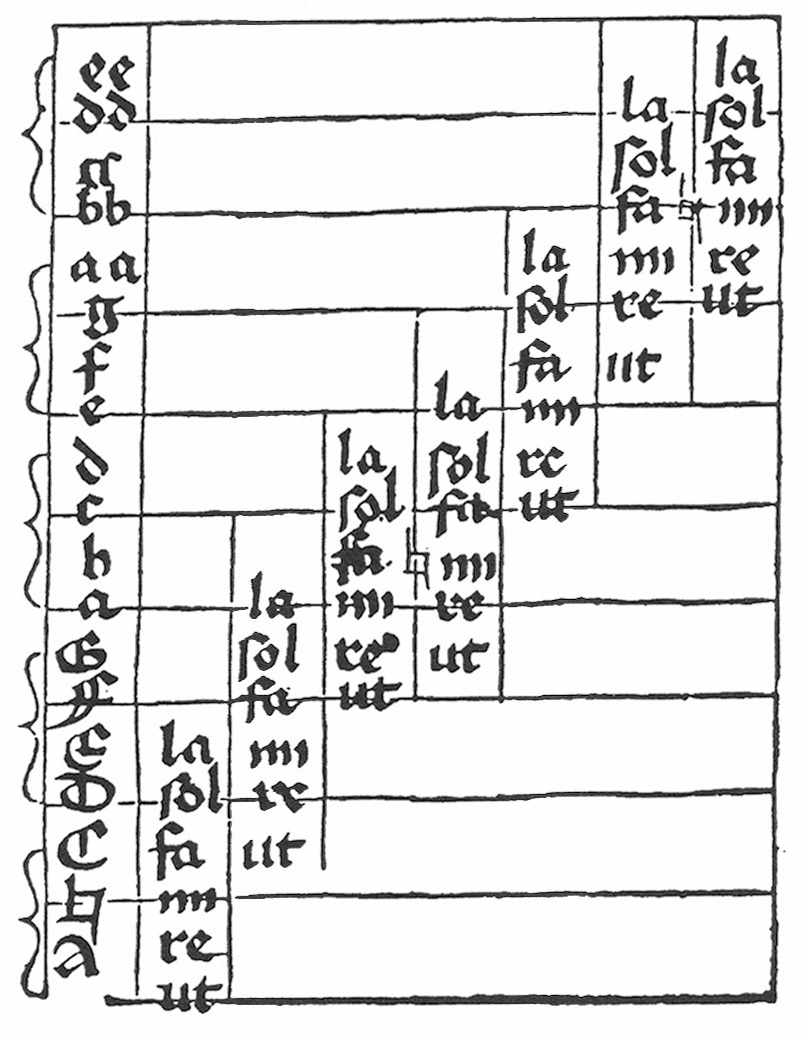

Cascading the three hexachords in alternating succession gives a full range of notes that make up the musica recta in Renaissance music. This collection of “regular notes” coincides in range with the modern grand staff, beginning with the bottom G on the bass clef and ending with the top E on the treble. The bottom G, named after the Greek letter and its placement in the hexachord durum, is the gamma ut. Hence, this system of notes came to be known as the gamut, a portmanteau of gamma ut, and which gave rise to the modern expression of “running the gamut”. The 1511 treatise, Musica getutsch by German theorist Sebastian Virdung, is believed to be the first written instruction manual on musical instruments. In it, Virdung provides the following illustration of the gamut:

As can be clearly seen, both B♮ and B♭ are included in the gamut, placing B♭ on equal footing with natural notes.

Going back to the Virgiliano finger chart above, a closer investigation reveals that what is labeled as “B” is in fact a forked B♭. This is indeed curious as B♭ does not typically belong to the D Dorian mode. One interpretation could be that this is simply a D-Aeolian scale, or D minor as we know it today, whose notes are D E F G A B♭ C. Early theoretical sources such as those by Pratorius or the French composer Philibert Jambe de Fer, however, suggest a strong tendency for the flute to play in transposed modes. Specifically, they point out that flat modes involving B♭ are better suited to the flute than others. Because of the physical construct of the Renaissance flute, simple and forked fingerings cannot be simultaneously made in tune. Since both B♮ and B♭ belong to the gamut, flute makers had to make a choice which one to favor. Fingering charts which selectively include flat notes strongly support the transposing narrative, and in light of this, it seems more plausible that the Virgiliano chart is in fact a transposed G-Dorian. Not only does the B♭ allow the flute to be in tune, but the D also provides a strong fifth above or fourth below the G final.

The Renaissance flute maintained its presence and popularity well into the seventeenth century and featured prominently in writings of Praetorius, Mersenne, and the alike. When a key was added to the transverse flute around 1670 to accommodate the emergence of a new style of wind music, the Renaissance construction began to fade and eventually gave way to an entirely new design.

Next up - the Baroque

The exact pitches of the consort is somewhat debated. The G-D-A combination is taken directly from Pratorius’s 1615 treatise, Syntagma Musicum; however, based on surviving flute music from the 1600s, some believe that the Renaissance flutes may have been transposing instruments.

Notice that beginning on the note G is the only arrangement including the note B that conforms to the tone-tone-semitone-tone-tone pattern while using only natural notes.